By Lanny Morgnanesi

My mind of late is wandering into dangerous places, forcing theories and ideas into my consciousness that lack convention, precedent, and true understanding. I can only off load them by sharing. And so, I write … about God and the universe.

Let’s begin with something simple: monotheism, the belief that God is singular.

I appear somewhat alone in my view that Christianity, especially Catholicism, is not monotheistic. This contention is more about the choice of words than about actual beliefs. If Christians decided they were pantheistic, it wouldn’t change much.

Supporting my argument is, or are, The Trinity – the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. That’s three, not one. The claim, of course, is they are one. But I see three, and never understood the logic of this division that is not supposed to be a division. Next there is the glorification of Mary, the mother of Jesus. In visions, she has appeared to people and passed along messages from God. Indeed, people pray to her and ask that she intercedes with God. If you can tell God what to do, and God does it, well, you’re pretty much a God yourself, even if a minor one, like the Greek Muses, or Iris or Eros. Next are the 10,000 or so saints believed to have performed miracles, who are prayed to daily and who watch over and guard particular villages, peoples, and professions.

Admittedly, that’s a lot of Gods, and it seems we like lots of Gods, even while insisting there is only one. The Jews haven’t fallen into this trap, especially not the tempting one where God takes on flesh. They only go so far as a burning bush. In early Islam, there was an attempt to deify the pre-Islamic goddesses known as The Three Sisters (Al-Lat, Al-‘Uzza, and Manat). In the so-called Satanic Verses of the Koran, they were said to be daughters of Allah. But these verses were later attributed to the devil and retracted, the sisters were sent packing, and Islamic monotheism was restored.

So it seems the multi-God legacy of ancient pagans, the Greeks, the Romans, and others remain firmly with us, even if we refused to admit it. While I can see the attractiveness of having a host of available entities for helping one navigate life, I accept a single creator, one powerful, governing force. I don’t want to use the terms he, him, or her, in reference to God, because I’m certain it is an entity without sex, nothing like an anthropoid, not someone we will eventually meet and gaze upon, and absolutely well beyond our elemental comprehension. We all would like to know God better, and Christians do through the human-form of Jesus Christ. In fact, they seem much more comfortable, much more absorbed with The Son than The Father, and that’s understandable. We know and understand humans but not an all-encompassing, unseen cosmic power.

I’m different, as I have suggested. I prefer the all-encompassing cosmic power. In my view, Jesus, as his story is told through scripture, limited his God-like self while on Earth. His main mission was to forgive the sins of man, save him, and grant him eternal life. Considering the vastness of the universe, with 2 trillion galaxies, and the mind-bending, unanswered question of why we are part of it, you might think Jesus would have talked a little about this, telling us what are job is, if we are alone among the stars, whether or not he will visit other planets, and what we will do in heaven, aside from worship, which, for all eternity, could get monotonous. If he chose not to explain such things, why wasn’t he at least asked?

As a God, Jesus could have done so much more to help us understand our purpose, our place, and our incredible surroundings.

As limited as his role on Earth may have been, the teachings of Jesus were enough to build a global religion. And whether it is monotheistic or pantheistic, it really doesn’t matter. For me, the problem with religion does not involve the number of gods, but rather the fact that the tenets and precepts are tightly packaged and handed to us by other men. Those men, for the most part, have done a good job, but I am cursed with the need to use my own brain to establish my own tenants and precept. I’m willing to borrow, but often I can’t.

In this regard, I may share something with Galileo, the great astronomer often called the father of modern science.. He said, “I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with senses, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use.”

And I haven’t.

If I may impose on the reader and indulge myself, I’d like to share the results of my thinking, my so-called religion, which, I fully admit, is not dogma but sheer speculation. It’s the best I can come up with.

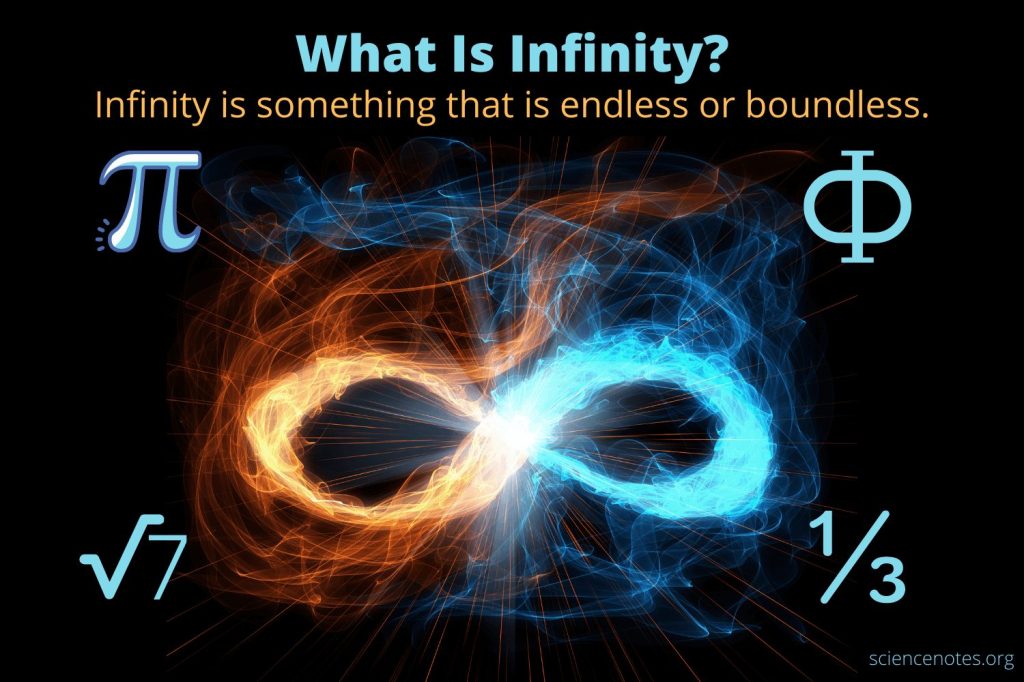

I don’t claim truth because my first proposition is that God is 99 percent unknowable. That is where I start. I start, basically, saying we can’t know, we don’t know, we probably were not meant to know, and we don’t have the capacity to understand. The truth, if it were revealed, would make no sense to us, like a complex mathematical equation would make no sense to a chimp. This is what I maintain.

I acknowledge the gifted prophets, who are so tied into the universe that they grasp the one percent know ability of God, and attempt to teach us. I respect scripture and its overarching message, and I believe in one God.

My second major precept is that God is perfect and acts perfectly. My God doesn’t need extra work and doesn’t do extra work. My God gets it right the first time. This is much more controversial than you might imagine. In my thinking, the perfect, unknowable God created the universe – whatever the universe is – in the exact way God wanted it, and that it does exactly what God wants it to do. So … God does not need to watch over us and intervene into our lives, nor does God need to course correct the universe. It’s like a perfect machine, doing what it is designed to do, and doing it perfectly. If you lose your car keys, or get sick, praying to God won’t help. The machine can’t hear you and won’t change for you or anyone. It’s mostly likely unattended

We can learn, grow, and become better human because of the preaching and parables of Jesus, a person in touch with God, but to think of him as God and distinct from The Father is, for me, too difficult. Jesus as God represents a kind of course correction, which I maintain is unnecessary.

I cannot envision a magnificent God creating a man, deliberately marking him with original sin, making him weak and prone to sin, then sitting back – if God can even sit – and watching to see if this creation can overcome its imperfections, as if, within God’s great universe, this was some kind of pastime or preoccupation, as if God did not know the outcome. I don’t think God would send a savior to help the poor souls he himself deliberately set on the wrong path.

God, to me, has better and bigger things to do than test or challenge the human specks inhabiting a small rock in an endless mega-verse. It is true the Greek gods enjoyed the antics and foibles of mortals, and used them as playthings, sheer entertainment. It is doubtful the real God does this. At least this is what I believe.

But let’s speak of the machine, God’s universe. How does it work?

I see two components at work: time and probability.

Time and probability, as established by God, keep the machine, without interference by its creator, on its mission, whatever that might be.

Let’s begin with probability.

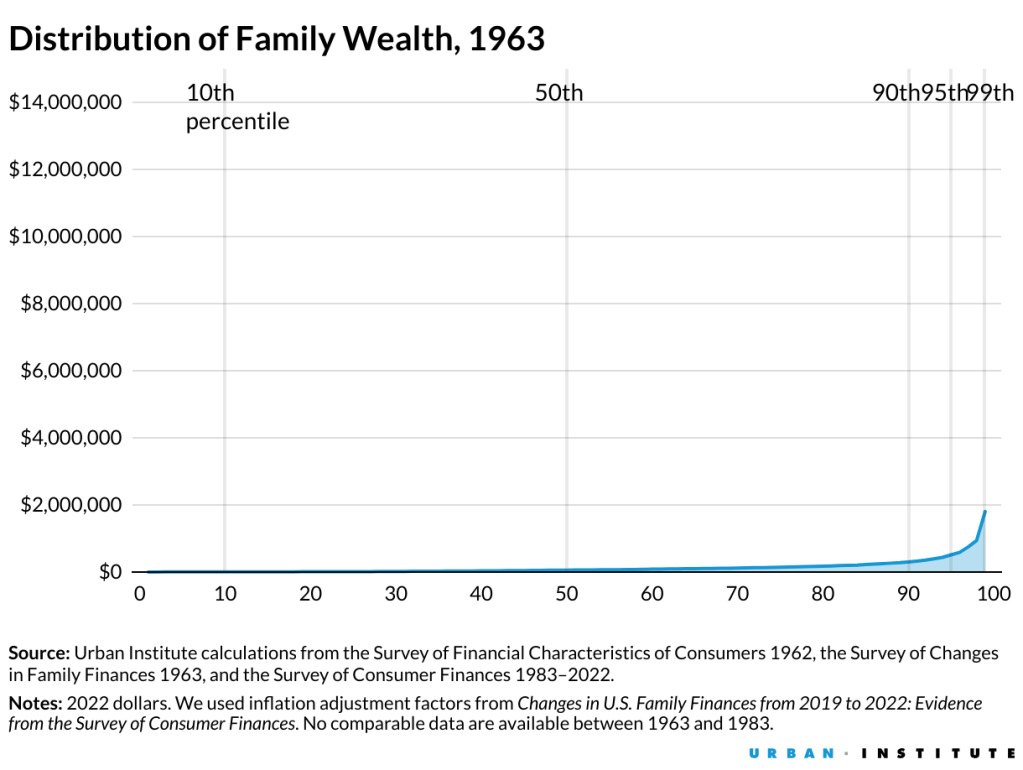

We are all familiar with probability. Consider the coin flip. If you flip a coin five times, there is a real possibility it could come up heads – or tails – all five times. But if you flip it 10,000 times, the law of probability will ensure that heads comes up about 5,000 times, as will tails, meaning the probability over many occurrences and over time is 50-50. That’s the law. Established, I propose, by God.

It’s the same with the building of the universe, its functions, and even us, the God specks.

God establishes what the end goal is, sets his probability for that goal, builds in an infinite amount of time, and lets the machine run. Maybe he wanted the dinosaurs to remain on Earth forever, and maybe he didn’t. Well, the machines put them here and probability, in the form of a massive asteroid that hit Mexico 66 million years ago, took them away. That may have been a low probability event (we don’t know), but if the existence of dinosaurs on Earth is a God goal, then over infinite time higher probability events will bring them back.

We are here now because of events whose probability we cannot be sure of, meaning we cannot be sure we are here to stay.

Probability also affects individual behavior. Probability, I propose, is mainly built into our DNA. Our DNA allows for the great majority of us to rise each morning, eat, get some kind of work done, and sleep at night – all while producing a heirs. Most of us will not commit murder. Most of us will not paint the Mona Lisa, or compose a Fifth Symphony, or figure out the speed of light. But some will. The probability exists for that. By my theory, our little world, for some reason, requires all these things, and so we have them. It needs people who are not afraid of heights so we call build towers and expansive bridge. And it needs people who ARE afraid of heights and risks so that we all won’t kill ourselves doing dangerous things. It also appears that, for some reason, at least here and there, we need both a Hitler and a Mother Teresa, and so God creates them, in the proper numbers, through the probability and miracle of DNA.

We are granted a degree of free will that allows us to decide whether or not to call in sick today or to finally clean up the back closet. But the engineer who designed the pyramids did not do so freely. Something within him forced it. God’s hand.

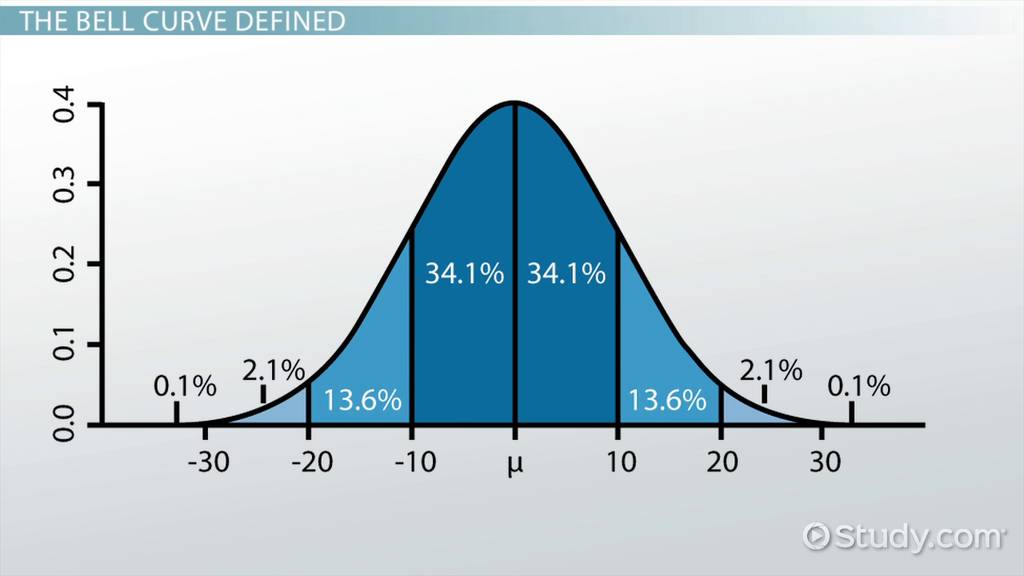

But I don’t envision a God with hands. I envision God as a bell curve. Gods is mathematical, and the universe and all humans operate like a bell curve, with lots of possibilities for common things and only a few possibilities for extreme things. A one end, where there is little room under the curve, is the horrible and disastrous. On the other end, where there is little room under the curve, is the wonderful and the exalted. As the curve rises and falls, the horrible and disastrous and the wonderful and exalted remain but decrease in occurrences. At about the middle to the curve, about 65 percent of the curve, where it is high and with room under it for most of us, are, roughly speaking, Mr. and Mrs. Normal.

And that’s how it all works. God is a bell curve, and his tools are probability and time.

I sort of faulted Jesus for not doing enough on Earth, and now – with respect – I will fault God for doing too much. God really over did it. When we look closely, we see that God incorporates tremendous complexity and beauty into everything – the big, the small, the in-between. God astounds us with our galaxy as well as the appearance of a blade of grass under a microscope. God obviously is not on a budget, has no time constraints, must be able to work quickly, cares about every aspect of the creation, never shirks or simplifies, never favors the tremendous over the nearly invisible, and provides the same rapt attention to everything. There is nothing simple about any of the aspects of the creation.

Bringing the ancient Greeks back for a moment, their logic convinced them that there was a starting point, a primal, singular component to all things. And so they invented the atom. It sounded good, and the best scientists of the modern world embraced it. Now, of course, we know there are a multitude of sub-atom particles.

The elemental component escapes us.

I could never out reason a Plato or Aristotle, but I must say my reason tells me something quite different about the primal piece of existence. I don’t believe it exists. Our intellect cannot grasp my idea, but I will share it nonetheless: There is no smallest and there is no largest. Find the largest and keep searching and you will eventually find something larger. Find what you think is the smallest, keep searching and you will find smaller. There will be no end to it. Small will begat smaller, and smaller will begat even smaller – and it will do so infinitely. There will be no end to it. The same for large. There is level after level after level.

The God of creation went in one direction and never stopped. Then he went in the other direction and never stopped.

Once you accept this idea, it follows logically that our God has a God, and that the second God has a God, and that God has a God … and so on, toward infinity, which we are incapable of understanding but seems to be the core of everything.

It reminds me of football, when there is a penalty close to the goal, you move the ball half the distance to the goal. If there is a second penalty, you again move the ball half the distance to the goal. Theoretically, under this rule, the ball would always get closer to the goal but never, ever reaches it.

Well, I’ve exhausted myself.

***

The great 17th-century philosopher, Baruch Spinoza, would disagree with all I have said about a plan, a machine, and an unknown purpose. He boldly proclaimed,“Nature has no intentions, no mercy, no plan – and calling this God is humanity’s refusal to accept insignificance.”

I accept my insignificance but still say there’s a plan. I just have no idea what it is.