(ALL NAMES HAVE BEEN CHANGED TO PROTECT THE GUILTY)

By Lanny Morgnanesi

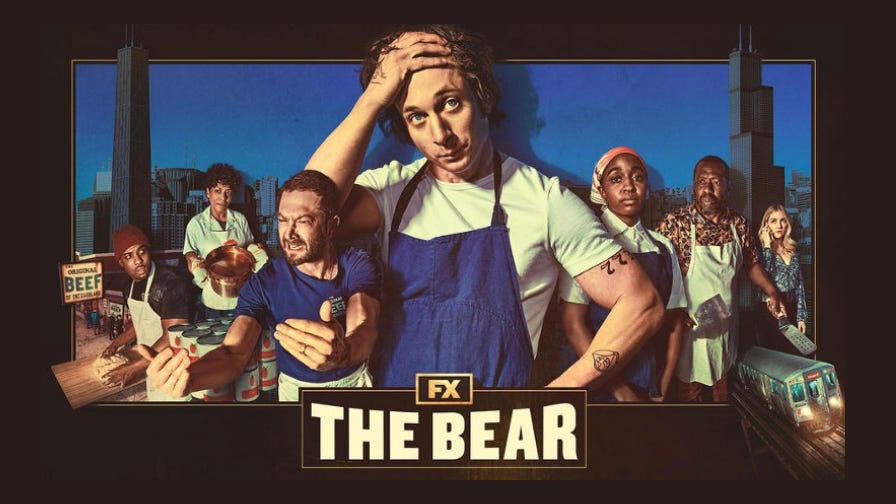

When I first tuned into the FX/Hulu TV show called The Bear, which just concluded its third season, I had no idea it was about a restaurant. Actually, it’s about two restaurants. Season One opens in a popular but gritty eatery best known for its Italian beef sandwich. Season Three ends in a classy, upscale joint (run by the same people) where the food on each plate is equal in size and weight to a Snickers. The Chicago-based series is about many things, including the obsession with perfection. But it is also about restaurant culture, a culture I was exposed to from age 15 to 22; a culture that I liked, appreciate, and understood. It was more than a culture; it was an education, one that was rare and unique.

And it all came rushing back after watching The Bear.

As a teen, I was unaware of myself. I knew I was not especially athletic, or especially smart, or especially funny. Other than that, I was blank. I didn’t know my quirks and idiosyncrasies, and assumed I didn’t have any. Early awareness, however, began developing after I took a job washing dishes at a place I’ll call De Luca’s, a small suburban restaurant that mostly served pizza, hoagies, steak sandwiches, and pasta dishes.

At De Luca’s, dishes were washed by hand, in a triple sink, with one empty, one having sudsy water, and one having a rinsing solution. On my first day, I found myself appalled that a fellow dishwasher was dumping sauce-covered dishes right into the sudsy water, turning it red, meaning all other dishes, even cleaner ones, would have to be washed in a tomato broth. Although I was the least experienced person at the restaurant, with no stake whatsoever in its management, I insisted that the saucy dishes be rinsed in the open sink before being placed in the soapy water, and I took it upon myself to change the soapy water at regular intervals.

On a busy Saturday, I expressed panic when the senior chef and consiglieri, the uncle of the owner that every called “Uncle,” tried dropping a large stack of saucy dishes into my sink. I stopped him abruptly and told him I needed to rinse them first. He looked at me with one eye and said, “OK Mr. Clean.” From then on, Uncle always called me Mr. Clean.

Next in my restaurant education, I was forced to ponder the conflict between morality and capitalism. It centered primarily on the quantity and quality of certain ingredients.

Between lunch and dinner, the dishwashers helped making meatballs. There was a set recipe to follow, and it included what I thought was an overabundance of breadcrumbs. I was outraged and started calling them bread balls. Clearly, the customer was being cheated (although they did taste good). Later, I was shocked to learn that on All You Can Eat Pizza Night, less than half the regular portion of cheese was used. What shocked me more was that no one cared. Furthermore, we were instructed to cut the lunchmeat paper thin. There were some complaints, but only because it took longer. All this led me to feel like an abnormal outlier, a crusading do-gooder that no one listens to. Then, the Uncle restored my confidence in mankind.

When I was cutting salami for hoagies, he happened to walk by with one of the managers. He saw what I was doing, paused, and looked around the table where I was working. He looked on a nearby shelf. He picked things up and looked underneath then. His head went left and right. The manager standing by his side asked, “Is something wrong?” Uncle answered, “I was just looking for the razor you use to cut this salami.”

Salvation. I was not alone. Morality and fairness can at least be a minority voice in capitalism. Humanity had been saved.

De Luca’s owner, let’s call him Tony De Luca, did have his moments of generosity. At Christmas, every employee – even lowly dishwashers — received a gift, a nice one. And every supplier, the truck driver or whoever it was that brought in the cartons of canned tomatoes, the heavy sacks of flower, the produce, received a fifth of whiskey. Once a year, Tony, a member of the Kiwanis service club, would donate hundreds of hoagies for the club to sell at its fundraiser. My young mind thought: Wouldn’t it be better to not do these things and instead make the meatballs meatier? Ultimately, I concluded, with no evidence, that what appeared like generosity was actually business decisions with a positive financial return; that goodness and kindness had only a little to do with it.

Thus was my early grounding in American capitalism and the world of commerce.

Next came my realization that common-sense rules, made sacrosanct and beyond question, had their purpose.

Growing up, I don’t recall being faced with rules that couldn’t be bent or challenged. But in the restaurant business, such rules existed, and while they meant more work for me, I considered them logical and important. I was more than willing to comply.

Three of those rules were:

- Break down all boxes before putting them in the Dumpster.

- When putting new supplies on shelves, rotate the old stock to the front.

- Do not leave the restaurant at night until it is thoroughly cleaned.

These rules, never written down, showed me people, even obstreperous ones, can be compliant in the interest of building a great institution or even a great civilization. This was an important lesson for a guy who had too many opinions of his own.

As a person who read books and intended to go to college, I felt superior to most of my restaurant co-workers. So, when they showed flashes of intelligence, as they often did, it caught me off balance. Once I was asked by a manager if I could operate a certain food processor. I said I could not, and he walked away. That’s when a guy named Freddy, who would spend his life in restaurants, told me, “You never say no. Say yes, and when they take you to the machine, say this one is a little different than the one you used. Ask him to show you the basics, and then teach yourself how to use the machine. You’re smart enough to do that.”

Basically, Freddy was telling me the adage, “Fake it until you make it,” which I hadn’t yet heard.

The educational level of De Luca workers was shown in their limited vocabulary, but some knew more than they let on. I recall a manager named Leon scolding a waitress, saying, “You know what your problem is? You’ve got ASS-mosis. Every time your ass sees a chair, it sits down.” After that, I had to assume he was familiar with the scientific process of osmosis, and Gpd knows what else.

Another vocabularic surprise came from a waitress who, during this period, might be described as “hard.” Rita used to hang out with her gang, drinking, smoking, and intimidating people on their “turf” behind a shopping center. She and I talked once about a De Luca’s employee who was fired. “The guy was a real jerk off,” Rita said, using a term often applied to people you don’t like. But then she added, “I mean he was literally a jerk off. He’d call you into the backroom and when you got there, he’d be stroking it.”

Writers and scholars often confuse the words “literally” and “figuratively,” but Rita, a young hoodlum, got it right.

De Luca’s was filled with thought-provoking characters and innumerable personalities. There was Ralph, who today would be persona non grata for his incessant use of sexual innuendo and inappropriate quips. We all thought he was funny, and – sorry — he was. Each year on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, he’d kindly tell every waitress, “Have a good holiday, but don’t get too much bird.”

Then there was Sidney, the brother of the owner’s wife. He was the kind of person only a relative would hire. Sidney fancied himself a tough, with-it guy who had learned everything from the streets. In truth, he was of genuine low intelligence, with a mumbled, tortuous way of speaking. He was difficult to understand, but he liked to talk. When he talked to me, I listened politely and just nodded my head.

Sidney took a liking to an obese young waitress with a clever mind and, unlike him, good verbal skills. She took to him, too, and they paired up for life – a short life. She died of kidney failure. He died trying to stop a robbery in progress.

I remember a Jewish guy who started working several years after I started. For some reason, he told us to call him Bean. He had shoulder-length hair and spoke like a Malibu surfer. One day, for a reason I cannot recall, I was contemplating the meaning of the Yiddish word “shiksa.” I didn’t know if it was a reference to all gentile woman, or just used to disparage them. During a slow period, I asked Bean, “What’s a shiksa?” Bean thought a moment, then pointed to a cute blonde waitress wearing a short skirt and showing cleavage. “You see her? That’s a shiksa.”

Funny story. Even funnier is he married her.

There was a pecking order at De Luca’s, with some holding high status and some holding low. Luther was one of high status. These were the ‘60s, and Luther was a full-blow hippie living the counterculture life. He was sarcastic and smart and knew things. At 19 or so he left home, married a hippie chick, got his own rundown apartment, plastered the walls with the covers of Rolling Stone magazine, and began working the grill at De Luca’s.

There was something about him, an air of mystery, or of danger, and he was treated like a celebrity by the other workers. Years later he came out as gay. Even later, he died of AIDS.

Old and young got along at De Luca’s. There was a middle-aged guy, Nico, who had been working lots of overtime. To perk himself up, he borrow some methamphetamine from a high school student working as a waitress. Then he borrow more, and more. I recall him up on the platform making pizzas on a busy Saturday night and the waitress who loaned him the drugs laughing loudly. “Look at Nico,” she said. “He’s speeding his ass off.” I just thought he was working fast.

Jocularity was always a part of work. A running joke or gag or bit would circulate and be repeated for weeks, until it was overused, dropped, and another gag adopted. There was a period when everyone called each other “cuz” – meaning cousin. Cuz this, cuz that. Hey cuz, get over here. Cuz, they are waiting for you. “Cuz” was used affectionately, to express like-mindedness, or ironically, to suggest strong disagreement. In cases of the later, the mock would sometime be answered with a sneering, “I’m not your cousin.”

I forgot what followed the “cuz” craze, but I was glad when it ended.

At De Luca’s, we were not all family, but we were close. Over time, we grew together, sharing large parts of lives. That happened with me and one of the partner’s daughters, let’s call her Melissa, who sometimes worked as a hostess.

When I first met Melissa, she was probably (hard to remember) 17. I may have been 19. Melissa was a special project. She was being groomed by her father, Nicholas, and Tony De Luca for the world of Show Business. She was their investment, and they expected a large payout. Several days a week, her father would shuttle her off to New York for dance, singing, and acting lessons. To protect their investment, Nicholas and Tony sheltered Melissa from boys, keeping her too busy to have time for them and directing her down a path they could not follow.

But one New Year’s Eve, everyone within and even without the De Luca circle was going to a huge party at a local night club. Melissa begged to be included. As a compromise, possibly as a controlled experiment, her brother-in-law (who also worked at the restaurant), enlisted me as her date. I was happy to oblige.

On New Year’s Eve, fresh through the door of the club, Melissa, whom I don’t believe ever drank, started doing shots. One after the other after the other. She was drunk in no time. After a dance or two, she grabbed me and led me out to my car. Then she jumped on me like a feverish cat. It was quite exciting. In the midst of that pleasure came a disturbing thought: I could loss my job. Worse, I could destroy Nick and Tony’s investment and they’d murder me. Neither possibility helped the mood.

Fortunately or unfortunately, there was a bang on my car door. It was the brother-in-law, who ordered us back into the night club. Yes, a controlled experiment.

In the aftermath, Melissa and I dated a little. On Saturday nights after closing, her father would finish up the bookkeeping while we’d wait in the car and neck. That was fun. But the most fun came for me one Saturday evening at a place called Paulie’s Starlite Ballroom, which was more of a bar than a ballroom. Saturday was a work night for me, Melissa and her father. However, an arrangement had been made that after closing, we would go to Pauli’s and Melissa, even though she was underage, would perform. And we did just that. I didn’t quite know what to expect, and I didn’t anticipate anything special, and nothing special happened. Even so, the simple experience of it, once I comprehended it, gave me a Sinatraesque feeling that put me on a cloud and transformed me into something I never thought I could be, even if it was only in my imagination.

There I was. Nineteen years old. At 2 a.m. Inside Paulie’s Starlite Ballroom. Being served shots and beers – for free. With my girlfriend up on a stage looking and singing like an angel.

Who was I? Obviously, someone very cool.

All from a humble beginning as a restaurant dishwasher.

When I watch The Bear, with all its gut-wrenchingly realism, I sometimes tear up. I did that during the Third Season’s finale, about the closing of a famous Chicago restaurant. There is a “funeral dinner” held to honor the restaurant, and restaurant people from all over town attend. When they filmed this scene, they included verité-like testimony from actual chefs. Toward the end, Olivia Colman, the actress playing the owner of the closing restaurant, gives a speech. She says of all the years and all the food, the one thing she will never forget are the people.

I was jubilant on my final day at De Luca’s. By then I was an assistant manager making pizzas. As I prepared to depart, there was no sadness, no melancholy, no regret. I just wanted to get the hell out of there, knowing that I would never again have to spend hot summers standing in front of two 450-degree ovens. My new destination was the University of Missouri, where I would earn a master’s degree in journalism. I looked so forward to a future where I would do something important and serve people who were hungry for news and information – not food.

But having now watched The Bear, I realize everything I’ve done since De Luca’s has been impacted by De Luca’s, and that my memories of Tony and Uncle and Bean and Freddy and Luther and Sydney and sweet Melissa and all the others are much stronger than of any professor at Missouri, or of any high dignitary I covered as a journalist. I also realized that the invisible energy and palpable excitement that invades and dominates a packed restaurant on a Saturday night, even to someone washing dishes, is indescribable, euphoric, and almost impossible to duplicate.

One final note.

In the early ‘80s, about a decade after I last saw Melissa, I was walking through the lounge at an Atlantic City casino. There was a stage and on it was a band fronted by an attractive, stylish woman. It was my old girlfriend, and she saw me. When the number ended, she ran off the stage to hug and kiss me. The audience watched and, God bless them, applauded.