By Lanny Morgnanesi

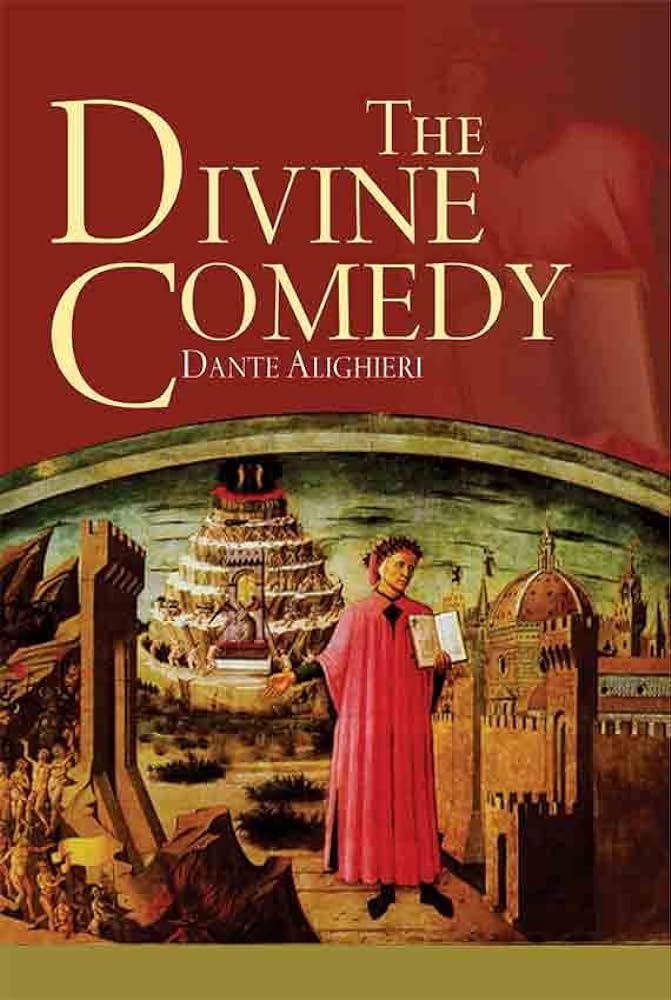

In 1990, I wanted to name my new-born son after a writer, or at least an Italian. In the end, we named him after an Italian writer. Dante Alighieri. Just Dante. Not Alighieri. And because of this, I vowed to read Dante’s most famous work, the acclaimed Divine Comedy, written between 1308 and 1321 and divided into three parts, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. When I was gifted by my young son with a nice leather-bound copy, I let it sit on the shelf to marinate. Or maybe I was just intimidated. When I decided to open it, it wasn’t there. Lost forever.

Thirty years later, I am reading a free, digital version, an 1867 translation by poet William Wadsworth Longfellow. It is considered one of the best. By coincidence, at this very same time, PBS is airing a series on Dante and The Divine Comedy. The series is easy. The book is hard.

You can’t just read the book You must look things up … constantly. There are scores of other books and websites to help with this – understanding the references, the personalities from history, the Greek and Roman legends, the pagan gods, geography, and so much more — and still it remains hard.

The work is considered one of the finest in all of literature, even 700 years after it was published. I find this remarkable because I’m certain Dante wasn’t writing for us. For him, in my estimation, it was a strictly contemporary work aimed at a small audience, the people of his native city, Florence. I drew this conclusion because with the billion who have died and gone to hell, Dante, during his visit there, run into about three dozen people just from his little part of the world. There are others, like Ulysses, Mohammed, and lots of classical Greeks and Romans. But for Dante, hell was very much like old home week.

His encounters include those with Florentines whom history remembers, as well as some whom history never knew. A few were involved in provincial scandals (like the two adulterous lovers inspired by the romance of Lancelot and Guinevere, who were murdered by the woman’s brother) or committed poor behavior (like the glutton Ciacco). These characters no doubt were a source of 14th century tongue wagging. But now? For Dante to include them means he was not intending to entertain readers in the far future. He doesn’t even provide much context or background or explanations, assuming his readers know the full story. Often, there is just a casual hint, or the drop of a single name. For example, when Dante enters Purgatory, he is greeted by a person he obviously expects his readers to know. He never names the person, only the woman that person loves, Marcia, and the city he comes from, Utica. Apparently, his target audience knew, or were expected to know, that the person from Utica who loved Marcia is the famous Roman orator and statesman Cato.

Confession: I did not know. I had to look it up.

Obscure as he may seem to us, Dante wanted to reach the widest possible audience of his day, and that included the nobility and the common people. This required a revolutionary approach, and Dante was more than willing to take it. Instead of writing in scholarly Latin, he wrote in the vernacular or vulgate, basically street talk, the dialect of Tuscany. And because of this, and the influence of his work, a form of Tuscan eventually became Italian and the language of a unified nation. Aside from its poetry, this is one reason why The Divine Comedy is considered a literary landmark.

If you read it closely, and don’t take its spirituality too seriously, you might find it quite temporal, an act of earthly vengeance by the author, who makes a habit of using the Inferno to inflict pain and punishment on his enemies. Context is needed here. Readers need to know that the poet had been a victim of Florence’s ceaseless civil war between the factions known as the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. He was a Guelph (although they later split as well), and when his group lost power, he was exiled from Florence and sentenced to death should he return. One of his enemies was named Farinata, a Ghibelline military leader and aristocrat. In hell, Dante conveniently entombs Farinata, for all eternity, in a coffin of fire.

A writer can get great pleasure doing that.

At times, however, he could be merciful. He spares a fellow name Buonconte by putting him in purgatory, allowing him to cleanse himself of sin and reach paradise. Buonconte was no friend of Dante. He was a military strategist who literally fought against Dante at the Battle of Campaldino in 1289. According to Dante’s telling, Buonconte accepted Christ at the time of his death, which I guess makes all the difference. So no punishment there.

Aside from punishing his enemies, Dante places a few people he liked in hell, including his teacher, a known sodomite, but he expresses sympathy and sadness for him.

Following the then-teachings of the Catholic church, Dante condemns to hell everyone in the world who was born before Christ, and therefore did not worship Christ. He places the virtuous Greek and Roman figures there, in the tame, unthreatening, limbo portion. These include Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Homer, Horace, Cicero, Seneca, Ovid, and, of course, the poet Virgil, his underworld guide. There are always exceptions, and one of them is Cato, the Roman politician and stoic known for his virtue and defense of the old Roman republic. Cato is in purgatory, but he probably will not get to cleanse himself and go to heaven. Rather, Dante gives him a job of sorts. Cato is a greeter who welcomes and instructs the new souls.

Although Dante, as the writer, condemns to hell those who followed the Greek and Roman gods, he shows immense respect for these deities, as if he, too, were a follower. He seems to worship them and acknowledge them as if they were real. In fact, he punishes those who blasphemed against Zeus, the supreme god, known to the Romans as Jupiter or Jove. In one unusual passage, Dante appears to call Jesus Christ by the name Jove.

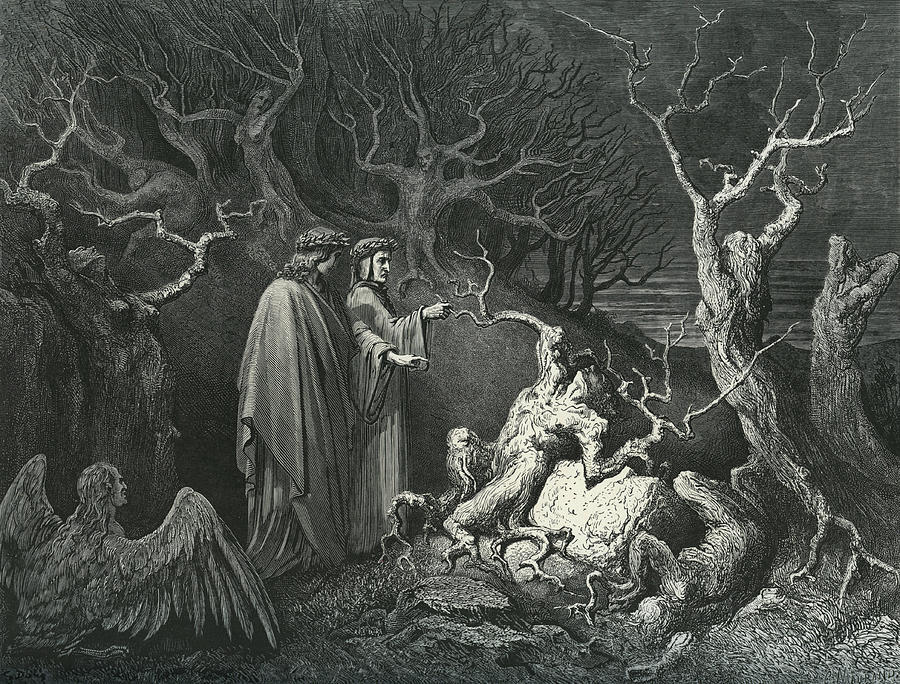

Let’s get back to the punishments, which range in severity depending on the sin. If you were gluttonous, you are tormented with ceaseless rain. If you were lustful, there is ceaseless wind. For the really bad, you could be continually pecked by bird-like creatures, or forever bitten by dogs, or submerged in boiling blood, or be torn apart, or forced to stand head-first in stone bowls and endure flames upon the feet. While we think of hell as hot, the worst level is a frozen wasteland. In addition to all this, Dante, as poet, sometimes punishes with a type of irony known as “contrapasso,” (to suffer the opposite). False prophets who claim to see the future, for example, have their heads turned backwards on their bodies, so it is impossible for them to see what lies ahead. That kind of thing.

Indeed, above all, The Divine Comedy is a poem, a work of art. And, at least in the Italian, it rhymes. It rhymes in such a complex fashion that, to keep their sanity, most translators of Dante don’t attempt to rhyme. Longfellow didn’t. The technique Dante used is called Terza Rima, or third rhyme. In the original Italian, each stanza is three lines. The first line rhymes with the third, then the first and third lines of the second stanza rhyme with the second line of the preceding stanza – and continues this way throughout. It’s ABA, BCB, CDC, DED, and so on.

This means the poet never gets a fresh start. As he moves on, he must craft new information based on words he already has used. It’s difficult to imagine writing a graceful or even coherent passage using this technique, yet Dante did it.

While I find The Divine Comedy utterly remarkable, I find it astonishing that Dante’s 14th century readers (and those who heard the poem recited by bards and troubadours) understood and appreciated the frequent references to Greek and Roman mythology. Dante uses them matter-of-factly and with confidence, as if he were communicated in the most simply, easy-to-grasp fashion. I sense he, while writing, was certain these allusions, descriptions and analogies would be as easily understood as the Tuscan version of “hello.” What is perplexing, almost depressing, is that these magnificent references, these beautiful literary devices, these moral tales of virtue, honor, tragedy, and comedy, are, for all practical purposes, impenetrable to us. Without the guide of a scholar, The Divine Comedy, in all its wonder, means little to us.

With the advent of modernism and the passing of the classical period, the elite and the common have lost the cultural bearings on which our civilization was built. And so we walk with half-empty souls, rejecting what had once been given to us, leaving behind the magic of our own humanity.

I envy the cobbler, or the butcher, of the Florentine farrier who maybe didn’t have an education but was washed daily, through frequent and copious tellings, in the stories of genius.

The concubine of old Tithonus now

Gleamed white upon the eastern balcony

This is from the purgatory section of The Divine Comedy. Very beautiful, but pretty much a casual throw-away line of introduction. What does it mean? It simply means: The dawn arrived. But today’s reader has no way of knowing that.

Tithonus is the key to understanding this well-crafted little stanza. In Greek mythology, Tithonus was a Trojan prince. The goddess Eos (the Roman Aurora) fell in love with him, took him for herself, and asked the god Zeus to make him immortal. In asking, she neglected to specify that she wanted him to remain young. And Zeus, with a dose of trickery not uncommon when gods grant favors, allowed him to live forever but required that he age. To the distress of his mistress, he became decrepit.

Eos, the disappointed lover, is the goddess of dawn. She dresses in a saffron-colored mantle and arrives in the sky each morning on a chariot, casting out the darkness and making way for Helios, the sun god, to bring on a new day. Know that and read again:

The concubine of old Tithonus now

Gleamed white upon the eastern balcony

Consider another simple passage that for us is complex. Most today are aware of the constellation Gemini. Most are aware that Gemini refers to twins. But most would not grasp the meaning of this:

Whereon he said to me: “If Castor and Pollux

Were in the company of yonder mirror,

That up and down conducteth with its light …

It’s a reference to the heavens. Castor and Pollux are the twin brothers for which the constellation Gemini was named, so Dante here seems to be talking about the constellation. But the story of Castor and Pollux is deeper and illustrative of an unusual scientific phenomenon called heteropaternal superfecundation. You see, the twins are only half-brothers. They have the same mother but different fathers. Their mother was the mortal Leda. Castor’s father was the mortal king of Sparta. Pollux father was the god Zeus, who raped Leda. The story tells us that the ancients obviously knew two eggs, in rare cases, can be fertilized around the same time by two different males. And they also knew they could use the skies to education and inform.

I say and explain all these many things having read not even half of The Divine Comedy. Now, it is time to return to the pleasant drudgery of those pages.

Before leaving, I’ll add one thought. It concerns the frigid ninth circle of hell, where a giant-sized Satan resides, frozen up to his waist in ice, waving his bat-like wings to maintain the cold. He has three heads and is chewing on Brutus, Cassius (the assassins of Julius Caesar) and Judas Iscariot. My question: With the much-later arrival of Adolph Hitler, which of the three would Satan spit out?

Even hell can change after 700 years.

Lanny Morgnanesi is a journalist and author of the novel, The King of Ningxia.