The New York Review of Books sat on the table face up, showing the lead item about James Baldwin. This was odd, since Baldwin died a quarter century ago. No new books from him.

“As a writer of polemical essays on the Negro question, James Baldwin has no equals,” the review said.

The Negro question?

Oh. This was not new. This was old. It was a copy of the first edition of the New York Review of Books, reproduced on the 50th anniversary of the publication. The Review was launched in 1963 as salve to a citywide newspaper strike. The most prominent authors of the day contributed. They did so on short notice and for no pay.

What a time that was!

Ideas and making a statement were more important than making money.

As a collective voice from the past now being read in the present, the Review of Books gives more than a few hints of intellectual unrest. The best minds of the day seemed to be laying the groundwork for a coming cultural break with convention and the status quo.

It’s right there, interwoven amidst the literature.

Those doing the writing were the avant-garde, and people listened to them. Looking over their names, it is difficult to recall writers today with reputations as large. Among the contributors were Norman Mailer, William Styron, Robert Penn Warren, Susan Sontag, Gore Vidal, Paul Goodman, Robert Lowell and Jules Feiffer.

If any group reflected the spirit of the times – or perhaps the coming spirit — this one did.

As did the books they reviewed.

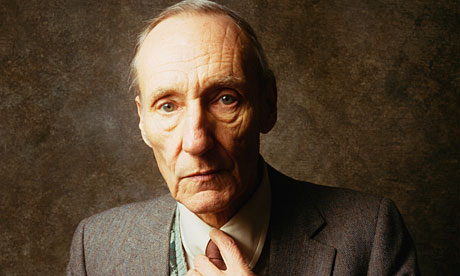

Included was “Naked Lunch” by William Burroughs, the grandfather junkie to the Beat writers. “Naked Lunch” is perhaps one of the most unclassifiable novels in the English language. The story – often bizarre and fantastic — takes place inside the head of a man taking a drug cure from a quack. At one point in his career Burroughs would write his prose on paper, cut it up then randomly reassemble the pieces

“Naked Lunch” was reviewed by Mary McCarthy, whose books include “The Group” and “Birds of America.”

At the close of the review, she deals with the “pained question that keeps coming up like a refrain” – Why is this book being taken seriously?

Her answer is that for the first time in recent years, a really talented writer meant what he said.

This was the coming era.

Some of the celebrity reviewers, those with the larger personalities, were overly tough on their colleagues. Normal Mailer, always pugnacious, said “That Summer in Paris” by Morley Callaghan was “dim” and mostly without merit. One passage, however, saved the book, Mailer said, because it exposed the true character of novelist Ernest Hemingway, who two years earlier committed suicide.

The tale has Callaghan, who boxed in college, getting into the ring with the much larger Hemingway. F. Scott Fitzgerald was the timekeeper. In a round that went long, Callaghan flattened Hemingway. Fitzgerald blamed his poor time keeping.

“Oh, my God,” he said. “I let the round go four minutes.”

Hemingway, perhaps from the canvas, answered, “All right, Scott. If you want to see me getting the shit knocked out of me, just say so. Only don’t say you made a mistake.”

To me, this shows meanness and poor sportsmanship.

To Mailer, who also boxed, it led him to concluded, “There are two kinds of brave men. Those who are brave by the grace of nature, and those who are brave by an act of will. It is the merit of Callaghan’s long anecdote that the second condition is suggested to be Hemingway’s own.”

In essence, Mailer was calling Papa a closet coward, and he cited his suicide as evidence of this cowardice.

Then there was Gore Vidal. He described John Hersey’s book, “Here to Stay,” as “dull, dull, dull.” Hersey was trying to invent something called “New Journalism,” which later would boost the careers of people like Tom Wolf and Hunter S. Thompson, but Vidal criticized him for cramming too many facts into his sentences.

John Updike is one of America’s best writers but Sir Jonathan Miller, a Cambridge graduate who did books, plays, movies and TV, said Updike’s “The Centaur” was “a poor novel irritatingly marred by good features.”

These reviews pretty much stuck to literature, but an unusual number referenced the Cold War and voiced the fear of imminent doom. It was hard to miss the Soviets. One reviewer discussed four books on the economy of our then-mortal enemy. Another reviewed Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s short gulag novel, “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

Robert Jay Lifton, in a review of a compilation called “Children of the A-Bomb,” said, “The thing we dread really happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But the world resists full comprehension of this event, symbolizing massive death and annihilation.”

He and others suggested that faith in the future was fading, and that without change mankind’s time was limited.

Reviewer Lewis Coser said education and information no longer were the answer.

He called the well-informed person “a cheerful robot.”

“The increase of information may indeed have led, contrary to the belief of the Enlightenment, to a decrease in rationality,” he said.

A remarkably forward-looking book carried the harmless title, “The Exploration of Outer Space.” It written by A.C.B. Lovell and reviewed by James R. Newman. Both lauded the development of radio astronomy as a way to finally understand the composition of the universe. They believed recent findings made it almost certain that other solar systems contained life and that future contact was possible.

But there was darkness overlaying this optimism. The review expressed a grave fear that humans, if they don’t destroy themselves first, one day would destroy life on other plants, either deliberately or through contamination.

The review ends this way:

“”I myself do not find the prevailing space-race chauvinism and the threat to other planets as horrifying as the threat of global extermination. Nor do I derive consolation from the thought that if our managers turn the earth info a lifeless stone other forms of life will continue elsewhere in the universe. But I am impressed with Lovell’s deep sense of responsibility about life everywhere, and I wish there were many more scientists like him.”

And that’s the way it was in 1963.

Coming would be Dylan, hippies, communes, the counter-culture; Burn Baby Burn, Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30; a refusal to be bought and sold; hope I die before I get old.

By Lanny Morgnanesi