The first real understanding of my value as a worker came during a company Christmas party.

I was a young reporter for a family-owned media company. My fellow employees and I had already received the gift of a free turkey, and now there was this party, grand and lavish.

It was a time when newspaper margins were around 40 percent. Printing a newspaper was like printing money.

The party was held in a big banquet hall. Hundreds attended. There was a generous buffet, music, dancing and an open bar for the entire evening.

In general, the company did well by its employees. The founder was a tough, bull-headed union-buster, but when I worked there raises were given four times a year, the food in the cafeteria was subsidized and supervisors were honored at an annual dinner.

Upon the death of the old man, his four grown children took over. By chance, I was sitting with one at the Christmas party. She was somewhat shy but sincere when she said to our table, “All of you are responsible for making this company what it is. It would be nothing without you. My family owes everything to you. Our success is your success.”

Prior to that, I had seen myself as an expendable, replaceable cog.

But this co-owner, this daughter of an entrepreneurial risk-taker, was shifting my view. I hadn’t recognized it yet, but she knew that without workers a hundred printing presses could not produce a single paper.

Still, she was neither ready nor willing to change the rules and divide the profits among workers. That’s a different ideology, one totally alien to our system, one that threatens and offends.

Then I went to New York City and found out it wasn’t.

I was still learning the way of the world and on this visit to see friends I discovered how lawyers became partners.

My friends were a former reporter and her boyfriend lawyer. He didn’t go to dinner with us that Saturday night because he was working on an investment banking deal. He was trying to make partner.

When we met up later at a bar, he was in good spirits and had no complaints. As an explanation for missing dinner, he told me a joke: “Why do investment bankers love Friday? Because it is only two more work days until Monday.”

I envied his chance to become a partner. Now that I think of it, he probably was the first person I knew who was capable of using hard work to earn equity ownership in a company.

Why was law different from other professions? To begin with, there is no huge investment needed to start up, nothing like a printing press. Also, lawyers tend to see themselves as professional equals. And there probably is some precedent, a near-ancient tradition, of taking on partners rather than employees.

What’s more, it is easy for the good ones – those who bring in big clients — to leave and hang up their own shingles.

A factory worker doesn’t have that kind of leverage.

But if there exists a universal law of fairness, a standard morality for the value and worth of labor, then leverage shouldn’t be a factor.

Of course, there is no morality in the marketplace. If people will work for substandard wages, that is what you pay them. And so unions came to be.

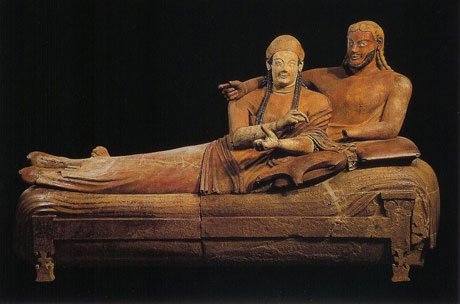

Unions got their start in ancient Rome

We think of unions as a modern concept but the idea and practice go way back. The founders of Rome, in 753 B.C., may be partially to blame. As Rome grew and incorporated other provinces, the new citizens didn’t integrate. They stayed in their towns, kept their habits and traditions and failed to adopt a Roman identify. So an edict was issued requiring people to relocate to districts organized around trades. If you were a carpenter, you lived among all carpenters.

Ethnic differences faded.

Naturally, trade associations formed. It was a new unifier.

In time, these associations became quite powerful.

Even the kings of France had to contend with them. In an age when candles were the chief source of lighting and a significant expense in a large palace, money could be saved by letting them burn to the end. Practical, but the guild in charge of candles wouldn’t allow it. It required that candles be replaced when half burned.

Unions in the modern era continue to be associated with self-serving, costly inefficiencies. Unlike the lawyers who must enrich their firms in order to become partners, unions too often weaken their companies, making workers liabilities rather than assets.

And companies today are quick to get rid of liabilities.

What unions are good at, however, is their ability to show management the true value of labor. By unifying the powerless, power is created. In speaking with one voice – “no we won’t work for poverty wages” – unions effectively alter the marketplace. They grant the common folk a degree of dignity and allow them to pursue happiness.

But with global competition so fierce, it has become impractical and unwise for unions to advocate uncompetitive practices. What they should advocate is efficiency, innovation, profit and partnership – true equity partnership. Unions gave us the weekend but if the incentive of partnership is applied (making Friday two work days until Monday) companies could get them back.

Would companies actually make their worker’s partners? Under the current climate, no. Even discussing the idea seems ridiculous and beyond farfetched.

But why?

In the golden age of unions – after resistance that included shooting strikers — companies decided there was enough growth and profit to meet the demands of organized labor. With profit in mind, there was a willingness to share. Henry Ford would benefit if he could keep cars rolling off the assembly line and meet the heavy demand.

And besides, workers with money buy things – like cars.

Walter Reuther knew the middle class fueled the economy.

(There’s a great story about Walter Reuther, leader of the United Auto Workers, being shown an automated assembly line. In a competitive dig, Henry Ford II asked him, “How are you going to get those robots to pay union dues?” Reuther retorted, “Henry, how are you going to get them to buy cars?”)

For the most part, the willingness to share is gone.

According to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities and many other sources, a significant income gap between classes existed from the 1940s into the 1970s, but it did not grow. But after the early 70s and up to today, income concentration at the top increased dramatically. The last time the disparity was this great was prior to the Depression.

Various sources, including University of California at Santa Cruz Professor G. William Domhoff, in his blog “Who Rules America?,” report that in 2010 about 1percent of the U.S. population possessed 35 percent of the wealth. The top 20 percent had 89 percent, leaving the bottom 80 percent with 11 percent.

Also reported in various places, including the Los Angeles Times, is that from 1993 to 2012, income of the 1 percent rose 86.1 percent while income of the other 99 percent rose 6.6 percent.

As wealth became concentrated at the upper tier, billions in cash was stockpiled by American corporations.

In March, Forbes set the total at $1.45 trillion and listed the top 10 holders of cash, including:

Apple: $137 billion.

Microsoft: $68.3 billion.

Google $48.1 billion.

Pfizer $46.9 billion.

What changed?

For one, the labor market.

When Apple is ready to roll out a new iPhone, poor farmers in Katmandu drop their plows and fly to factories in Malaysia. This is not a rhetorical sentence.

Journalist Cam Simpson documents Apple’s labor supply chain in an incredible piece of investigative reporting for Bloomberg Businessweek. His story tells how labor brokers fan out to the poor countries of Asia when Apple launches a new product. The people they find pay them for jobs and keep paying as the process continues. Often, they pay with borrowed money and go deeply in debt.

One was Bibek Dhong from Nepal. He paid a single broker the equivalent of six-months wages. The fee secured him a job in Malaysia with Flextronics, one of Apple’s chief suppliers. Before he could pay off his loans, production shifted to another country (better performance) and he lost his position.

His passport was held and he could not get home. He feared he would be arrested. Before he received help from Flextronics, he ran out of money and nearly starved.

Not exactly a union shop.

But as China has realized, when companies get richer, when commerce thrives, when corrupt leaders and their families amass great, visible wealth, expectations rise and workers lose their complacency. They demand more and often get it, until the factories move to a more accommodating country.

Sooner or later, corporations are going to run out of countries.

Sooner or later, a floor will form under the global labor market. From there, workers will stand.

That’s when corporations are going to need a new plan.

And that’s why I’m suggesting one now.

In the U.S., people are finally waking up to the subtle yet systematic dismantling of the middle class, which has been occurring for decades. With less spending power, average families find it difficult or impossible to send their children to college – once the gateway to upward mobility. Those who do make it to college find it hard to get jobs when they graduate.

The bleakness and lack of opportunity, the malaise of our times, is truly settling in.

Books are being written with titles such as, “The War on the Middle Class,” “Screwed: The Undeclared War on the Middle Class,” and “The Betrayal of the American Dream.”

Income equality has become a topic in columns, blogs and editorial cartoons. The issue, once ignored, is now discussed by the president of the United States and the Pope. Billionaire Warren Buffett said that if class warfare truly exists, his class in winning. Even so, there are defections. One is global billionaire David Sainsbury, who calls for fairer wealth distribution through something called “progressive capitalism.”

To see inside this looming class crisis, look toward Seattle, the home of Boeing.

Timothy Egan, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and winner of the National Book Award, wrote an opinion piece in the New York Times Nov. 14 called, “Under My Thumb.” The title refers to Seattle’s position vis-a-vis Boeing.

Like many big corporations, Boeing hold jobs hostage as it demands and gets hefty tax breaks. As Egan points out, when anyone or anything shows resistance, companies like Boeing threaten to leave town.

Boeing is seeking concessions in exchange for keeping assembly of the new 777X jet in Washington State. For its part, the state of Washington provided a incentive package that included an $8.7 billion tax break, which Egan called the largest single state-tax giveaway in the nation’s history.

But Boeing also requires that workers accept cuts in pensions and health care benefits.

Unlike Washington, the workers said no.

Refusing to allow the “Walmartization of aerospace,” the machinists who would build the 777X turned down the offer by a 2-1 vote.

“I’m tired of being slapped in the face,” said John Gilman, who has worked at Boeing for nearly 40 years. “Building airplanes — it takes years of training and skill. The people who run this company used to understand that.”

In reaction to Egan’s piece, one reader commented, “This is just the beginning before Americans ‘storm’ any number of figurative ‘Bastilles.’ ”

Jump now, if you will, to the town of Richmond, California.

In Richmond, like most of the U.S., people were talked into taking home mortgages they couldn’t afford. When the housing bubble burst, they ended up owing more on their mortgages than their homes were worth.

Nothing unusual there.

What is unusual is the protective reaction, possibly unprecedented, taken by the town fathers on behalf of residents. Basically, they told the banks holding the bad mortgages to renegotiate the terms or Richmond would confiscate the properties through eminent domain.

Under this plan, the banks would receive 80 percent of each home’s current worth – much less than the original purchase price –and the town would reform the mortgages so owners can afford them.

Meanwhile, all across the country fast food workers are trying to nearly double their hourly wage to $15.

Not too long ago, the Occupy movement surprised everyone when it surfaced to protest almost everything. It stayed around much longer than anyone expected and started widespread discussion of the 1 percent and vast income disparities.

What else is out there waiting to bubble up? I sense there is a lot.

Nature and the human spirit, in time, tend to correct imbalances. I believe this correction has begun. When there is too much of one thing, the other thing comes.

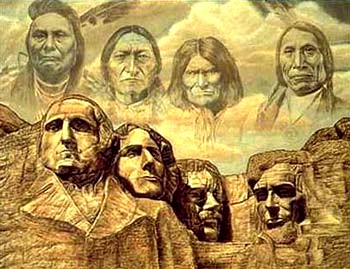

And when the other thing comes, I hope we are ready for it. We might prepare by realizing that we all have a stake in each other’s well being, that each plays a role in the ultimate success of our society and that respect and dignity should be afforded to all. We are a tribe – we humans — and members of a tribe should look out for each other.

Right now we don’t.

I say, let’s act more like partners. Let’s all rise together.

That means valuing each other properly and recognizing that all roles are important, that we’d be in big trouble if one day no one wanted to pick up the trash.

Providing an equity interest to all workers – even a thin, thin sliver – is progressive and revolutionary. It may even be moral, wise and an effective business strategy. But for it to happen, something cataclysmic must occur, or the vision of something cataclysmic must appear.

In the meantime, it is likely that agendas will slowly change (perhaps preventing any cataclysm). This fall, for example, Bill de Blasio was elected mayor of New York after saying he would trim the gap between rich and poor.

Other politicians, in a discovering of new voting blocs, may decide to do the same and relieve the working poor of its distress, better balance wealth and create a more secure, just and – I think – more prosperous society.

A person with disposable income, after all, fuels the economy and is less of a burden on government.

Tax policy, a major cause of the wealth shift, also will have to change. An almost whimsical proposal comes from Robert Shiller, who on Dec. 8 received the Nobel prize in economics. To stop inequality from rising, he suggests raising taxes on the rich whenever their share of income starts to grow.

Should any of this actually happen, it won’t come solely out of true enlightenment. As always, it will come mostly as a way to preserve and protect – through concessions – the self-interests of the powerful. This is OK. It will come through changing market forces resulting from a shift in culture, attitudes, expectations and action. Those forces, nearly invisible now, seem to be coalescing. I don’t think they can be stopped.

When there is too much of one thing, the other thing comes. That’s the natural law.

Lanny Morgnanesi

Tags: ancient Rome, Henry Ford, income inequality, investment bankers, labor, Lanny Morgnanesi, Middle class, minimum wage, one percent, unions, United Auto Workers, Walter Reuther, worker ownership

Philip Cafaro, author of “How Many Is Too Many? The Progressive Argument for Reducing Immigration Into the United States,” gives a thorough accounting of all this in a recent edition of the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Philip Cafaro, author of “How Many Is Too Many? The Progressive Argument for Reducing Immigration Into the United States,” gives a thorough accounting of all this in a recent edition of the Chronicle of Higher Education. There is, however, a consensus that a middle class, if one is desired, must be created, otherwise there will only be rich and poor. One was created in Europe during the 14th and 15th centuries. Unfortunately, the creative force was the Black Death — the bubonic plague that may have killed one out of every three Europeans (about 20 million). With the labor force devastated, there was upward pressure on wages and the ability of farmers to earn a much better living. Some reports say farm income increased by 50 percent.

There is, however, a consensus that a middle class, if one is desired, must be created, otherwise there will only be rich and poor. One was created in Europe during the 14th and 15th centuries. Unfortunately, the creative force was the Black Death — the bubonic plague that may have killed one out of every three Europeans (about 20 million). With the labor force devastated, there was upward pressure on wages and the ability of farmers to earn a much better living. Some reports say farm income increased by 50 percent.